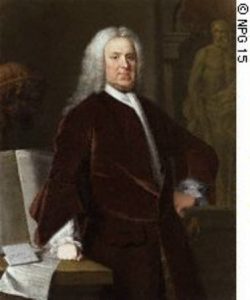

Dr Richard Mead of Harrold Hall:18th Century Physician, Celebrity & Medical Pioneer

Richard Mead (1673-1754)

A portrait by Allan Ramsay, oil on canvas, 1740.

On display in Room 11 at the National Portrait Gallery

“Foremost among the medical men of the last century, for his professional skill, his amiable manners, and princely munificence, ranks Dr. Richard Mead” (“Chamber’s Book of Days” 1869)

“…he lived more in the sunshine of life than almost any man.” Samuel Johnson

This image is obtained on licence from the copyright holder, The National Portrait Gallery, London and may not be reproduced, transmitted or stored in any form or in any retrieval system without the written consent of the copyright holders. The licensing and purchase of this image was generously sponsored by Harrold Medical Practice.

Introduction: Impact on the Modern World

Two and a half centuries after his death, Richard Mead still leaves an imprint on the modern world. There are scores of web pages devoted to his life and works. Eight portraits are owned by The National Portrait Gallery and other portraits are displayed in The Royal College of Physicians and The Foundling Hospital. His extensive collection of works of art, rare books, important letters, etc. may have been sold off after his death, but many of these now appear in museum collections or in other public places. Recently a collection of Richard Mead’s medals were sold at auction. In addition to his own published works, books have been written on his life and works and he has provided the subject or material for Phd researches.

Harrold Connections

Richard Mead’s connection with Harrold began when his second wife, Anne (daughter of Sir Rowland Alston) inherited Harrold Hall in 1732 from her aunt, Anne Joliffe. Richard Mead, already had his Bloomsbury home in Great Ormond Street and a country house at Old Windsor, Berkshire. Nevertheless, Richard and Anne frequently visited their Harrold home despite his busy professional and social commitments in London. Harrold Hall remained in the Mead family until Anne died in 1763 (Richard had pre-deceased her in 1754).

Early Beginnings

Richard Mead was born in Stepney in 1673, the eleventh child of Matthew Mead, a celebrated non-conformist minister. Having decided to follow the medical profession, he studied on the Continent (three years at Utrecht, a period at Leiden and then graduated from Padua in Philosophy and Physics in 1696). He then returned to London and set up his medical practice in the Stepney house where he was born.

In 1702 he published the work which was to establish his reputation, A Mechanical Account of Poisons. This work was based upon a surprisingly modern approach to his research methods, including experiments with viper venom, and it emphasised his strong belief that all physiological and pathological phenomena were the result of the laws of physics. In 1703 Richard Mead was elected to the post of Physician at St. Thomas’s Hospital where he was instrumental in persuading the wealthy Thomas Guy to found Guy’s Hospital when St. Thomas’s became overwhelmed by the rapid expansion of the population of London.

Still a young doctor, Mead was showered with honours and appointments; in 1703 he was elected Fellow of the Royal Society and to that institution he contributed a paper on the parasitic mite which causes scabies; he was appointed to read anatomical lectures at the Surgeons’ Hall; he was called to the deathbed of Queen Anne in 1714; two years later he was elected a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians and was Censor in 1716, 1719 and 1724.. Throughout this time his medical practice expanded rapidly.

Richard Mead: The Celebrated Physician

Following the death in 1719 of his first wife Ruth (whom he had married in 1697 and who was the daughter of a city merchant, John Marsh), Richard Mead moved home and practice to Great Ormond Street, where his house occupied the site of the present Hospital for Sick Children. The house had also been the practice of his friend, another famed surgeon, John Radcliffe.. Fashionable society sought his professional services and his patients included Sir Isaac Newton, Sir Robert Walpole (the first Prime Minister), The Prince and Princess of Wales, and Gilbert Burnet, Bishop of Salisbury. He travelled frequently into the countryside, including regular trips to North Bedfordshire and also dispensed medicines at an appointed hour from Batson’s Coffee House in the City. His income was said to have exceeded £6,000 per annum, a colossal sum in those days.

It was perhaps ironic that In October 1723 Mead delivered the Harveian Oration at the Royal College of Physicians, the subject of which was his defence of the position of physicians in Greece and in Rome as wealthy and honoured members of ancient society. Naturally this excited some controversy, especially in view of the affluent lifestyle of Mead and other fashionable doctors. In 1727 Richard Mead became Physician in Ordinary to George II and to Queen Caroline.

Richard Mead: Father of Preventive Medicine

In 1720, when there was a fear of the return of Bubonic Plague (an outbreak had occurred in Marseilles) Richard Mead was asked by the government to produce a paper on methods of prevention (perhaps one of the earliest attempts to produce a national health policy). The result was the publication of A Short Discourse Concerning Pestilential Contagion and the Methods to be Used to Prevent It. Nine editions of this work were subsequently produced. Its recommendations included practical needs to isolate the sick in proper places and methods of quarantine and fumigation.

Richard Mead had been an advocate of inoculation as a means of preventing Smallpox and in 1721 he supervised the inoculation of seven condemned criminals in Newgate Prison, all of whom recovered. This was sixty years before Edward Jenner revolutionised the prevention of smallpox by vaccination.

Richard Mead: Patron of the Arts and Bibliophile

Richard Mead was a patron of fine arts and an avid collector of paintings, statuary, coins and gems. His collection, including more than 10,000 volumes of rare and ancient books and manuscripts was housed in a purpose-built gallery in his Great Ormond Street house and he ensured that this was readily accessible to others. One such visitor in 1734 was Benjamin Rogers, Rector of Carlton and his daughter.

“…From thence we went to Dr Mead’s, saw his fine Library and Curiosities and Dined there, and returned to Mrs Trevor’s house at 7a clock.”

(Historical Carlton through the Diary of Benjamin Rogers published by Carlton and Chellington Historical Society 1999)

Richard Mead’s interest in botany was recognised by a plant being named after him – Dodecatheon Meadia – a native wildflower brought back from the American Colonies.

Its popular name is “Shooting Star -used as a rock plant in English gardens.

See also the pages relating to Anne Alston and Harrold Hall